Every project needs evaluation. Even though it might sometimes be considered as cumbersome or stressful for those whose work is evaluated, it is important that the merits and limitations of any given project are clearly laid out. A well-conducted evaluation ideally goes beyond highlighting the particular achievements of a program by delivering ideas for improvement. Furthermore it justifies the need to continue the efforts surrounding the project and its aims. It is commonplace that evaluation and feedback are employed during the last stage of the curriculum development cycle. However, it is well-founded that initiating evaluations in program development should be started as early as possible. The benefits are many with the central reasoning being that evaluating early on maintains and ensures that the chosen tools align with the planned outcome(s).

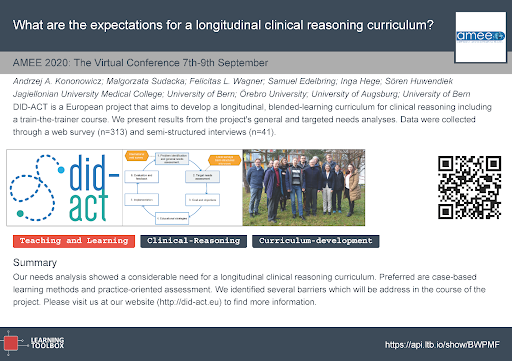

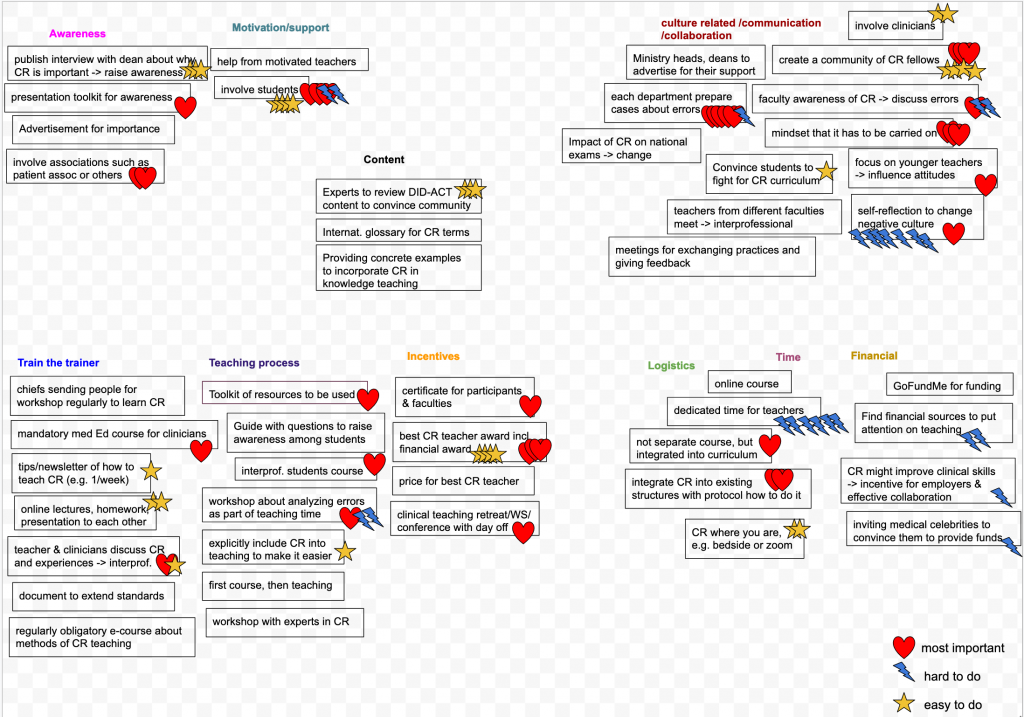

In terms of evaluation for the DID-ACT project, the Evaluation Work Package is a shared effort of the consortium partners. Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, is responsible for its coordination. Its first year of activities finished in December 2020 with a report published on the project’s website. During the first half of the year, the activities were focused on gauging the needs of potential users by developing a web survey to collect the specific expectations. From the data gathered, the DID-ACT project’s set of learning objectives and curricular framework were developed by another working group of the project. The goal of the second half of the year in terms of the evaluation work package was to propose a set of evaluation and learning analytic tools. Combined, these measure the planned outcome of the DID-ACT student curriculum and train-the-trainer course.

At the time of commencing our evaluation work, the specific set of learning objectives had not yet been set. Thus we first reviewed the literature in search of existing tools that measure participant satisfaction and perceived effectiveness of clinical reasoning training. This brought us the productive advantage and opportunity to reuse the outcomes of former projects. We experience this as an important point that demonstrates continuity and sustainability of research in this area. Our literature review identified a number of studies in which evaluation questionnaires of clinical reasoning learning activities were presented. Based on the analysis of the questions that aimed to measure student satisfaction, we were able to identify seven common themes of interest: course organisation, clear expectations, relevance, quality of group work, feedback, teaching competencies, and support for self-directed learning. We collected plenty of exemplar questions in each of the themes. Additionally, for the self-assessment questions we have assigned the gathered items to the DID-ACT learning goals and objectives.

Surprisingly our literature review did not yield any evaluation questions specific to clinical reasoning that could be used for our train-the-trainer courses. We resolved this challenge by broadening our goal. We adapted our search to include faculty development evaluation questionnaires that focused on honing teaching skills in general (not necessarily exclusively clinical reasoning). There was one evaluation tool from this group that caught our attention in particular: the Stanford Faculty Development Program Model (SFDP-26). We value its wide dissemination in many domains and clearly formulated set of 26 questions grouped in seven dimensions. An additional strength is that it has already been translated and validated in languages other than English, for example, in German.

An interesting discovery for us was a tool that measures the impact of curricular innovation following the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM). This tool, developed at the University of Texas, proposes an imaginative way of measuring the progress of curriculum innovation. It does so by identifying the types of concerns teachers voice regarding new topics. These concerns can range from disinterest, through concerns about efficiency of teaching of this element, and end with ideas for expanding the idea.

The CBAM model is based on the assumption that certain types of statements are characteristic to particular developmental stages when introducing an innovation into a curriculum. The developmental stage of introducing the innovation is captured effectively by the Stage of Concern (SoC) questionnaire. When collecting the data from a particular school the outcome is a curve that displays the intensity of concerns found within the seven consecutive stages of innovation. The value this brings is that comparing the curves across several institutions can help us visualise any progress implementing the curriculum is having. We find this visualisation to be akin to following how waves traverse the ocean.

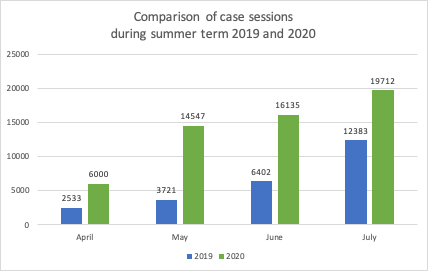

As the DID-ACT curriculum is planned to be a blended model of face-to-face and e-learning activities, we intend to use learning analytics in our curriculum evaluation. More specifically we will capture, process and interpret the digital footprints learners leave while using electronic learning environments. It is of course pivotal to be transparent about the purpose and to obtain consent regarding the collection of educational data. Upon receiving consent, computational power can be harnessed to optimise educational processes to the benefit of both learners and teachers. From the perspective of the curriculum developer, it is particularly important to know which activities attracted the most versus least engagement from students.

This information, when triangulated with other data evaluation sources, e.g. from questionnaires or interviews, allows us to identify elements of the curriculum that are particularly challenging, attractive or in need of promotion or better alignment. The learning analytics dashboards are viewed for our purposes a bit like a car’s dashboard where our fuel, odometers, speedometer display key information; for DID-ACT, analytics present a clear range of visualised progress indicators in one place.

We selected then analysed two electronic tools that will be used to implement the technical side of the DID-ACT curriculum: “Moodle” (a learning management system) and “Casus” (a virtual patient platform). Our goal was to look for the relevant learner data that could be collected. In addition, we intended to determine how it is visualised when following learner progress and trajectories. To systematise the process, we have produced a table we dubbed the ‘Learning Analytic Matrix’ that shows how engagement in attaining individual DID-ACT learning goals and objectives is captured by these electronic tools. Logs of such activities, like the opening of learning resources, time spent on activities, number and quality of posts in discussion boards, or success rate in formative questions, will enable us to map what is happening in the learning units developed by the DID-ACT consortium.

This is augmented by recording traces of some learning events which are characteristic to the clinical reasoning process. These events can be qualified as success rates in making the right diagnoses in virtual patient cases, student use of formal medical terminology in summary statements, or making reasonable connections in clinical reasoning concept maps. We also inspected the ways the captured data are presented graphically, identifying at the moment a predominance in tabular views. We foresee the possibility of extending the functionality of learning analytic tools available in the electronic learning environment by introducing a more diverse way of visualising evaluation results in learning clinical reasoning.

The collection and interpretation of all that data related to the enactment of the DID-ACT curriculum using the described tools is something we are looking forward to pursuing in the two upcoming years of the DID-ACT project.