Looking back at our last chunk of time in the DID-ACT project, we have a lot to be proud of and a lot to look forward to. One of the most exciting and hands-on aspects of this clinical reasoning curriculum launch is where we are right now: Pilot Implementations.

Train the trainer course on clinical reasoning

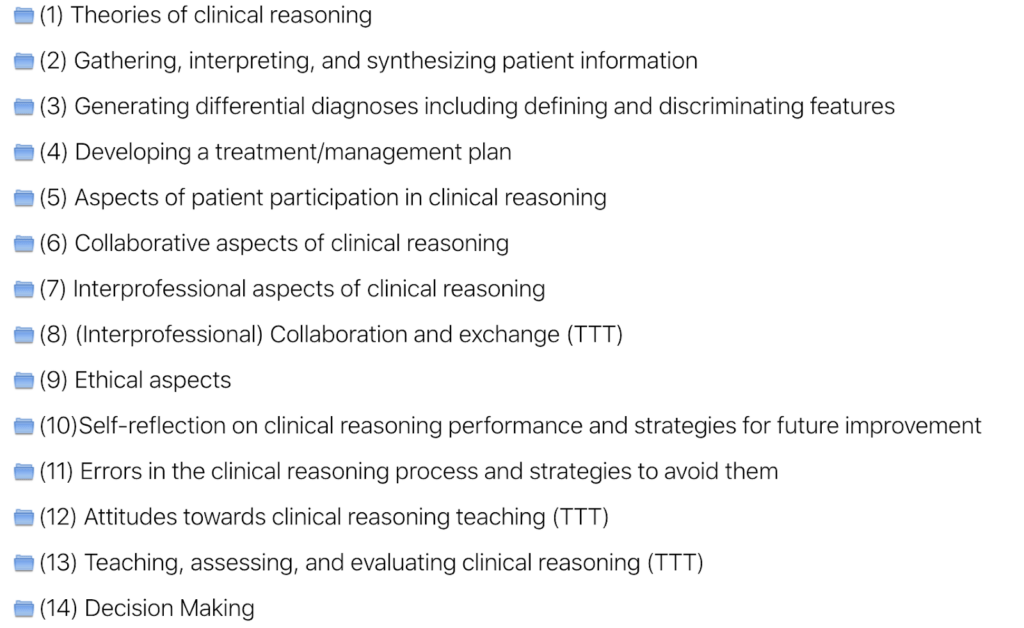

In our latest report published, Pilot implementations of the train-the-trainer course, we focused on the train the trainer learning units for our curriculum. These pilots were valuable and insightful in terms of helping the team iron out kinks in content, strategy, communications, etc. Overall, we had 7 courses that covered 4 different clinical reasoning topics up until the end of October. We are pleased to share that this made for a total of 69 participants who included professions such as medicine, nursing, paramedics, basic sciences and physiotherapy, from various partner-, associate-partner, and external institutions. We also had student participants. Overall the feedback was very positive. Next up is to take this feedback given and implement it into the curriculum.

Quality criteria for pilot implementations

Our quality criteria, which we were successful in achieving, were the following:

- More than 50 participants from partner and associate partner institutions, as well as external participants

- Covering a wide range of topics of the train-the-trainer courses that fit to the partner faculty development programs

- Piloting of at least two same learning units by 2-3 partners

- Thoroughly evaluated based on questionnaires for participants and instructors and learning analytics (in alignment with WP5).

Methods for a train the trainer implementation

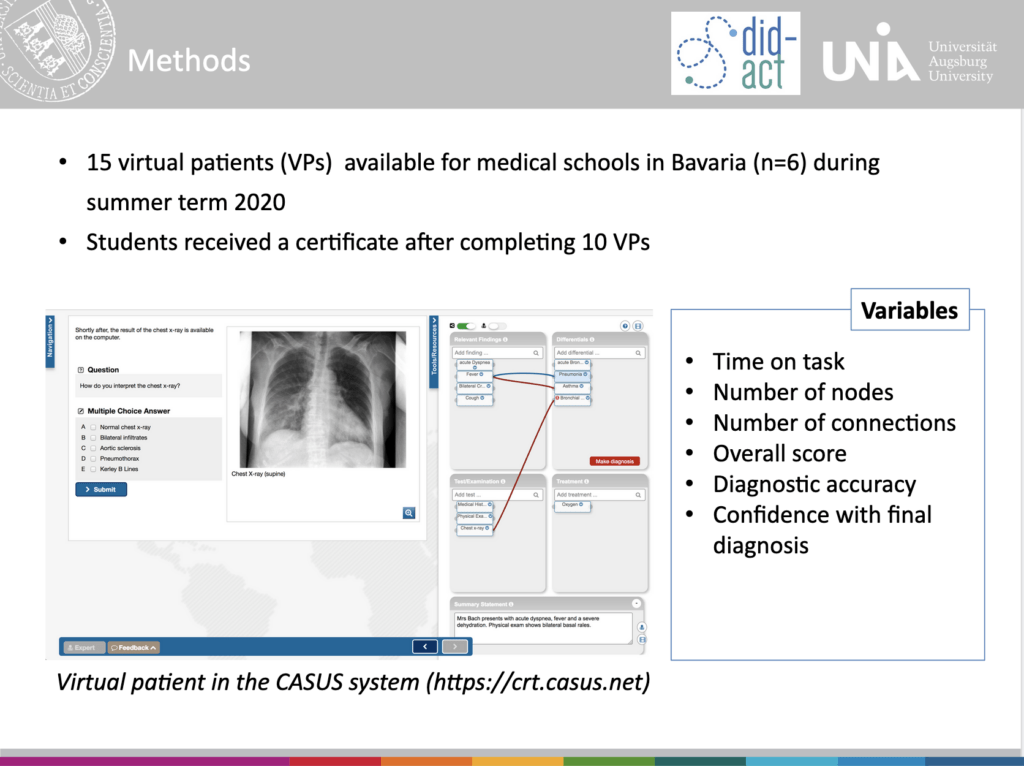

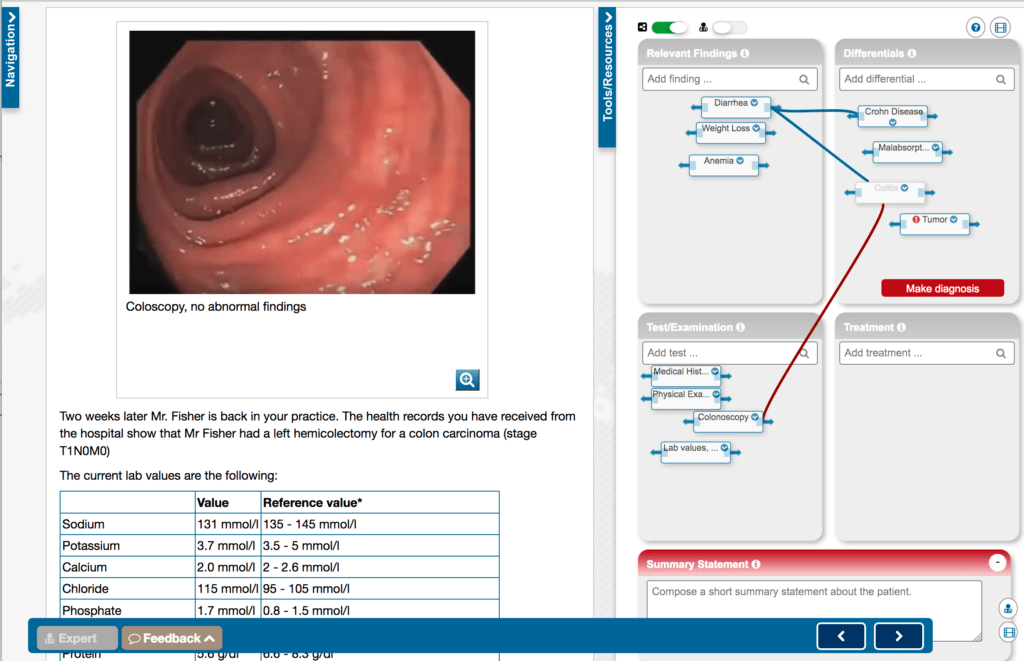

We used our chosen learning platform Moodle to host our blended learning curriculum. There were several steps taken to ensure implementations were as smooth and consistent as possible. It began with a succinct planning phase.

Planning phase

Most of the train-the-trainer courses were chosen in tandem with their student curriculum counterparts. This was done intentionally so that trainers would be adequately prepared themselves to teach the students. Each institution chose their learning unit based on their individual needs and requirements.

During this time, the consortium met on a regular basis to plan and ensure that quality criteria would be met. As well, alongside doing pilots within our consortium, we elected to have external participants as well for external applicability.

Implementation phase

The implementation happened differently at each institution and recruitment ranged from emails to specific cohorts to full public university call. During this time, each member was supported by Instruct to ensure that course access, structure of the pilots, and required facilitator resources were accessible and clear. This included a roadmap on how to use the Moodle platform as that was highlighted previously as an area with need support. Differences were also du to use of course forums and analysis of feedback within the learning platform.

Analysis and feedback phase

One of the deliverables for work package 5 was an evaluation questionnaire, as well as an analysis of the usage data. The former was given to participants at the end of the learning unit. Alongside this evaluation, each facilitator was given a short template to fill in for more qualitative reporting on their experience. Each of the responses was categorized and discussed together.

Results

In the end, we piloted 4 interprofessional sessions and 3 with external participants. Feedback was generally positive and otherwise anything that could be termed as less than ideal is being used as constructive feedback for further refinement. Our biggest wins were that the interactive aspect was found to be highly valuable and the facilitators from varied professions was appreciated. Our constructive feedback was around Moodle and Casus being unclear as tools, too little time, teaching topic vs teaching how to teach was a crunch, as well as how the conversation veered toward medicine due to the unbalanced participant professions (i.e too many phyisicans versus physiotherapists in one group).

Pilot implementation conclusions

Overall, the consortium deems this round of clinical reasoning pilot implementations a success. There are points we need to work on, such as Moodle clarification, additional tutorial video was already produced, and time constraints, which will all be addressed in the coming review period for the learning units. What’s more, the consortium will be delving during to the conclusions on the didactical and content-level for the learning units via the evaluation results reported in D5.2. These will all be brought forward during the overall revisions and improvements slated for D3.3 which begins in January 2022.