At the end of December 2020, the DID-ACT project consortium welcomed two things: the holidays and the successful completion of Work Package 2. This post aims to provide an update on what that entailed, what we completed, as well as provide a short overview of what we are going to be developing in Work Package 3. To begin, we will provide a brief overview of what we learned using the age-old rhetorical question: “How do you eat an elephant?” To which the answer is, “not in one bite”.

This rhetorical question is often used to illustrate how overcoming large and complex challenges is done by dividing them into smaller chunks. That when broken down into bite size pieces, these challenges are easier to manage. In the case of the DID-ACT project and beyond, every clinician, educator or researcher who has tried to describe the nature of teaching clinical reasoning, has realized this challenge. As a team, we most definitely learned this throughout work package 2 as we represent a collection of diverse professionals with the same ultimate goal, but with different ideas on how to get there.

When broken down further, we explored and learned how teaching clinical reasoning is a challenge that is inherently multifaceted. One facet, for example, is the complexity of a clinical situation, a second, is the need to grasp the nature of the varied competencies required to address the situation at hand, and third is how to support the learning of these competencies effectively.

Developing a clinical reasoning framework

Last fall the DID-ACT consortium developed a clinical reasoning curriculum framework that included clinical reasoning quality criteria. In addition to the above challenges, we emphasized having an interprofessional clinical reasoning curriculum. Our interprofessional framework was conceived with the input from different nations and educational cultures, all conducted online due to the current pandemic. So – similar to a complex clinical situation, we faced a plethora of challenges when producing and describing a clinical reasoning framework. This work led us to the development of two curricula: one directed to health professions students and one for teachers.

What makes a good clinical reasoning curriculum?

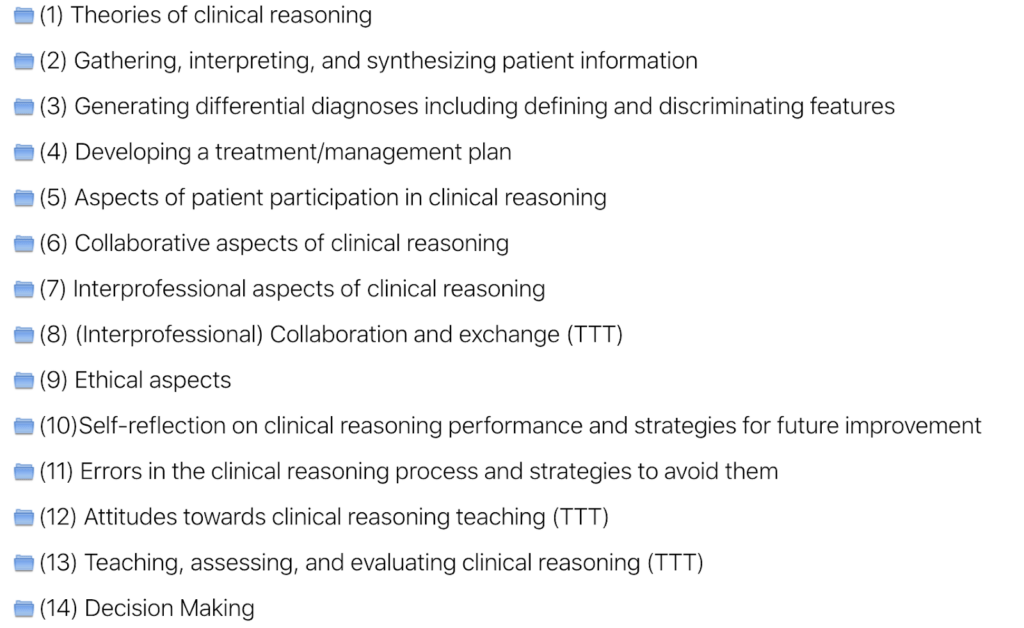

When we zoomed out to get a clear idea of the big picture, we noted a few crucial pedagogical aspects: a strong focus on student-centeredness; a perspective in which the student takes responsibility for their own learning process; as well as a strong connection to relevant clinical situations which means that knowledge and competencies were applied to context. We also noted that the philosophy of “constructive alignment” will be used when designing our clinical reasoning learning units. In practice, this means that the intended learning outcome should direct choices when designing learning activities; thereby creating a harmony between the clinical reasoning learning activities and how they are assessed. This means that the intended learning outcomes hold a central position when designing your clinical reasoning learning activities, assessments, and learning units overall. That is why we structured our interprofessional clinical reasoning framework according to ~ 50 learning objectives in an interdisciplinary consensus process.

DID-ACT’s Health Professions Education Framework

Did we eat the metaphorical elephant in this project phase? Yes!

By using our various knowledge and skills collectively, then by dividing the bigger task into parts and iteratively working in small and greater teams, we put parts back together to form a much clearer picture. Building from Work Package 1, we had a framework that is grounded in an interdisciplinary needs analysis directed towards a breadth of European health professions schools to launch from. When taking our learning into WP2, our work entailed bringing forward and evaluating a large amount of open learning resources for clinical reasoning based on our desired learning outcomes. It was essential that these learning resources were accessible and of a strong quality for our online clinical reasoning curriculum. When we tied our learning objectives, outcomes, assessment ideas, and open resources together, we created a well-rounded, interprofessional framework and the beginnings of an actual online clinical reasoning course.

At this point, you are most welcome to look at our identified learning objectives, the framework and our recommendations to current national curricular descriptions on our reports page. Hopefully you and your school can benefit from them in order to support explicit learning of clinical reasoning. There is also a collection of existing open educational resources to support you, your students or colleagues that support clinical reasoning.